A mother/daughter creation

Anticipating the birth of our granddaughter any day now, I've begun sorting through shelves and closets to locate storybooks, art supplies and games that have been tucked away for some time.

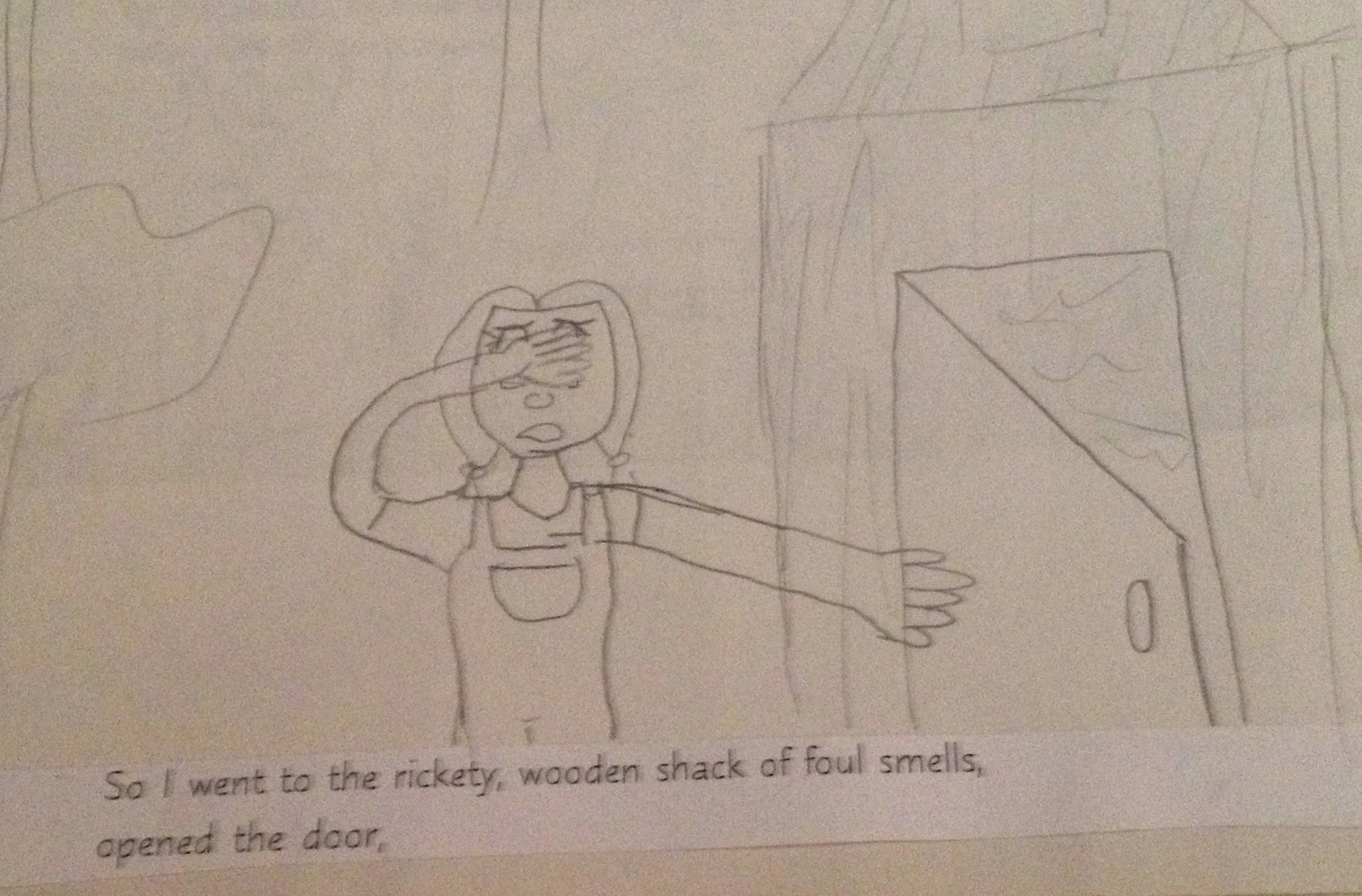

Today, I found a little treasure: a story that I wrote and my daughter, Moira, illustrated back in 1996. She was 10 years old. I was doing a fair amount of live storytelling at the time, and she and I used to do all kinds of projects together. This is a story I used to tell, and one day we decided to make it into a book.

I took pictures of the book's pages just now with my iPhone and posted them above. Here’s the text solo:

The Doonlobber Pesterfill

Written by Laura McHale Holland

Illustrated (above) by Moira Kathleen Holland

If and then, in a time of tuggle doodles and whatever wherefore to now considered, there lived a graphnel swapfnicker sort of thing. Yes, colorful indeed was this graphnel swapfnicker sort of thing, with iridescent turquoise eyes, purple-silver snout, and red nostrils.

Of course, that was long ago now, for I was almost six years old when I saw the thing slithering beneath the leaves — brown, red and gold — that had already fallen to the ground, though it was mid-July, and the grass was high, and the baby frogs were not yet jumping across the meadow, Uncle Bill's meadow, that is.

The grapnel swapfnicker sort of thing appeared while I was avoiding as long as possible a trip to the outhouse with its daddy long legs crawling, hungry horse flies buzzing, lizards lurking, and other creepy things mucking about.

All morning I was a knight in shining armor ordering rows of pansies to their doom at the hands of my sister, Ruthy-Bea, who was a sorceress, only until noon though, when she became Elvis Presley, and I had to be Marilyn Monroe swooning on the nearby maple stumpunless we found an arrowhead along the way, which would change everything, you see. Then I would be Elvis, and she would be Marilyn, and we would argue down by the tool shed. But instead of an arrowhead, I found a rusty dagger, which must have fallen from a lost pirate ship, and I swaggered off with my treasure down the hill to the dry creek bed, for Ruthy-Bea and I had no rules about daggers.

While I played suave swashbuckler dueling a crew of mutinous grasshoppers, Ruthy-Bea cornered a baby rabbit up in the peach orchard, put it in a cardboard box, and began instructing it in the esoteric beauty of the times tables. The graphnel swapfnicker sort of thing snorted at my feet, cleared its throat with a great rickety-rumble-dumble and said, "She's got the wrong idea there with the times tables. Rabbits like the ABC's, nothing more, nothing less."

I looked down at its nail-file sharp claws emerging from the leaves, and I said, "How would you know? You're just one of those graphnel swapfnicker sort of things sticking your snout out for some air."

"How do you know I'm not a doonlobber pesterfill?" it sneered.

"Uh, I studied them last summer, and everybody knows doonlobber pesterfills live in the dirt mounds in the dense woods over there. They never come out."

"Oh, yes they do, every year in mid-July, and they eat sweet little girls like you."

"Like me?" I was suddenly shrunken in spirit, for I had not really studied about doonlobber pesterfills, and I suspected this graphnel swapfnicker sort of thing knew that. "Oh, no, they don't like girls like me," I said. "I'm sneaky and sly and not at all good tasting."

"Who, then, would be good tasting?" the thing queried."

“I'm sure Ruthy-Bea up in the peach grove would be, for she is good, sweet and kind. She tastes better even than chocolate ice cream, if you like to eat people, of course."

And then with a bam-boom-schram-a-flam, the grapnel swapfnicker sort of thing rose up from the leaves in the creek bed, and he tore off his head, which wasn't his head at all, but a mask, and beneath was a foul smelling critter with slimy scales on his lumpy skull and sunken eyes oozing what looked suspiciously like cherry jello.

It grabbed me with its steely claws, threw me into the creek bed. I landed in a cloud of dust, and the thing zip-zipped and bip-bipped like the wild mouse carnival ride up to the peach orchard.

"Ruthy-Bea, watch out!" I screamed. "It's a bona fide doonloabber pesterfill heading right toward you."

Ruthy-Bea picked up the box with the bunny inside and she ran, but she didn't watch where she was going, and she ran smack into a peach tree. The box flew into the air, across the meadow, and through the open rear window of my father's Ford Galaxy, as he drove up Uncle Bill's driveway on his way back from a run to the Foster Freeze.

The doonlobber pesterfill grabbed Ruthy-Bea; its slimy fingers closed in around her neck. I ran as fast as I could. I had to save her. She wasn't really good, sweet and kind. She was sneaky and sly just like me.

I touched the rusty, trusty dagger to my leg — I hoped it would magically speed me up the hill — and cazoom-varoom-daploomb, there I was right at the pesterfill's big, stinky feet. I bit his bristly legs, pulled scales off his back, pried his fingers loose from Ruthy-Bea's neck.

But then he whop-glopped me with his triple-jointed, rubber-tire tail. The tail stretched and wrapped around Ruthy-Bea and me. Ruthy-Bea bit down hard on the creature's wheezing nose. He lost his balance, and the three of us rolled down the hill into the dry creek bed — fists, scales, twigs, and hair flying everywhere.

The doonlobber pesterfill landed on top of me, he wrenched the rusty dagger from my fist, and he held it right above my heart.

Then water, sweet cool water, rained down upon us. The doonlobber pesterfill moaned and groaned and melted right into the leaves, winking one of his turquoise eyes at me before he disappeared. I looked up, and there was my father spraying us from above with Uncle Bill's garden hose. How did he know it would melt the doonlobber pesterfill, I wondered.

Ruthy-Bea and I jumped to our feet and raced up to hail him, our hero, who had just saved us from yet another near-death experience. We each grabbed one of his legs and kissed his trousers right at the knees.

"Look at the two of you," he growled, "a couple of hooligans. Why, I can't take you anywhere before you start fighting and making a mess."

"But there was …" Ruthy-Bea began.

"Please, no excuses," he said. "And what about this thing?" He brought a hand from behind his back. By the ears he held the baby rabbit dressed in melted butter-pecan ice cream, chocolate fudge, and whipped cream “You know when you come to Uncle Bill's you're not supposed to catch the animals. They're wild, and they don't like it. Why don't you ever just play with dolls?"

I took a big gulp. "We can explai—"

"I don't want any of your far-fetched explanations; we're going home right now."

"Aw, Daddy," Ruthy-Bea and I lamented.

"Oh, and Shrimp," he said, pointing a finger at me, "Go to the outhouse before we leave. It's a long ride back to the city."

So I went to the rickety-wooden shack of foul smells, opened the door, and to my surprise, there were no daddy long legs crawling, no hungry horse flies buzzing, no lizards lurking, and no other creepy things mucking about. And I knew it was the doonlobber pesterfill who had gotten 'em all, for it was mid-July, the grass was high, and there were no sweet, little girls to eat, not at Undle Bill's anyway.